by Jennifer Larson

“Do you find it easy to get drunk on words?”

“So easy that to tell you the truth, I am seldom perfectly sober.”

–Busman’s Honeymoon (1937)

To my mind, only two sleuths in the mystery genre exert a never-ending fascination: Sherlock Holmes and Lord Peter Wimsey. (I admit to a brief flirtation with Nero Wolfe and his orchids, and a great admiration for Father Brown, but eternal fascination? No.) Having recently re-read all the Wimsey books in order after a gap of decades, I find myself impressed anew by Dorothy Sayers’s development as a mystery writer. The early books (Whose Body?, Murder Must Advertise) focus on ingenious methods of murder and concealment, while the later ones (The Nine Tailors, Gaudy Night) embed Sayers’s clever puzzles within more profound explorations of character, conscience and human existence.

Like Holmes, Wimsey is a bit larger than life because of his extraordinary intelligence and powers of deduction. Wimsey is more charming than Holmes, and (yes) more whimsical, the family motto being “As my Whimsy takes me.” He is vulnerable to the occasional nervous attack, having been shell-shocked in the trenches of WWI. For all his refined palate, Savile Row tailoring, wealth, social position (brother to a Duke) and perfect Piccadilly flat, Lord Peter is more human than Sherlock. Where Holmes is impervious to romantic feeling, even in the case of beautiful Irene Adler (the only individual, male or female, who ever outwitted him), Wimsey falls hard and instantly for Harriet Vane, a writer of detective stories caught up in a real murder case and accused of the crime.

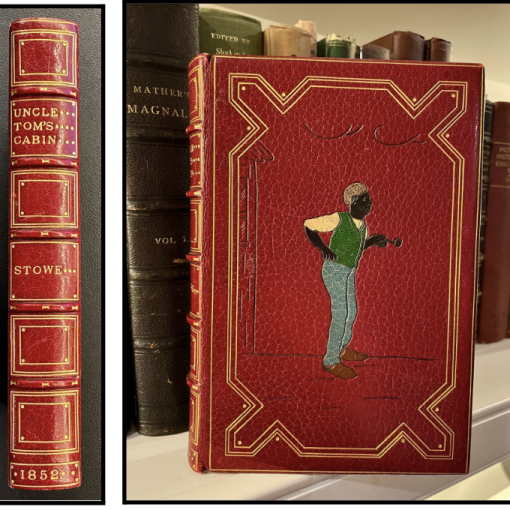

But Harriet was not Peter’s first love. Oh no–first there were the books, unless detection itself is to claim first place. His passion for books is recognizable to every fellow bibliophile. On page 1 of the first Wimsey novel, Whose Body? (1923), we meet a man in whom the bibliomania rages unrestrained. Having forgotten his catalogue for the “Brocklebury sale” (perhaps fictitious, for I have found no reference to it online), Wimsey directs his taxi driver to return to 110 Piccadilly that he may retrieve it. He thus returns home in time to receive a phone call notifying him of the bizarre case of a corpse found in a Battersea bathtub wearing only a pince-nez. Had he been forced to choose between attending the book sale and plunging immediately into the Battersea mystery, he might have been hard-pressed, but fortunately Wimsey’s man Bunter is competent to bid on Wimsey’s behalf. He is keen to acquire “the Folio Dante” (Florence, 1481 according to Sayers’s footnote), Wynkyn de Worde’s Golden Legend (1493) and Caxton’s The Four Sons of Aymon (“the 1489 folio and unique”). Sayers further informs us in the footnotes that Lord Peter’s Dante collection is “worth inspection,” for it includes the Aldine Dante octavo of 1502 and a Naples folio of 1477.

Evidently Lord Peter collects early printed books, especially incunabula (those issued up to 1500). He is particularly fond of Dante and books printed in England, and he tends to prefer literature to the other subjects, such as theology and medicine, commonly found in 15th century printed books. Sayers fans will know that she herself was a Dante scholar, producing a translation of The Divine Comedy, yet this happened late in her life, during the 1940s and after. It is an interesting twist of fate (or the psychology of the author) that already in 1923, the young Sayers had identified Dante as a core element of Wimsey’s collection.

Not surprisingly, Bunter proves a competent agent. Who among us would not give our left arm, or at least two lesser-used digits, to enjoy the devoted service of a Mervyn Bunter? He secures the Dante and the Caxton Four Sons of Aymon, saving his employer £60 in the process. Later in Whose Body? Wimsey casually mentions having paid the princely sum of £750 for a single book. According to various online calculators, this amount in 1923 is the equivalent of £56,837 today. And indeed, a copy of Wynkyn de Worde’s Golden Legend auctioned at Christie’s in 2021 fetched £52,500. English incunabula have held their value.

Lord Peter’s library at 110 Piccadilly is enviable, “one of the most delightful bachelor rooms in London.” A jewel-box of rare editions, it boasts a decorative scheme of black and primrose, Chesterfield sofas, a black baby grand piano, a roaring fireplace, and vases full of red and gold chrysanthemums. Into this sanctum wanders Wimsey’s friend Detective Inspector Parker, in the first of his many appearances in the series. Parker, it turns out, is well-educated enough to appreciate Wimsey’s books, but prefers Wimsey’s sister (Clouds of Witness, 1926). A practical man, he evinces no trace of the bibliomania, but takes a professional interest in Wimsey’s cases, which often overlap with his own.

More book-talk appears partway into Whose Body?, as Parker is breakfasting with Wimsey and reveling in Bunter’s “incomparable coffee” with toast and marmalade. Bunter draws his master’s attention to the sale of “Lord Erith’s collection,” and, intrigued by the mention of an Apollonios Rhodios (Florence, Lorenzo de Alopa, 1496), Wimsey asks him to send for the catalogue. This is the first we hear of Wimsey’s interest in Classical authors, Apollonios being the author of a third-century BCE Greek epic about Jason and the Argonauts. The volume in question is the editio princeps, i.e. the first time Apollonios’s book was put into print. Lest we fellow bibliophiles worry for his success at the sale, Sayers informs us in a footnote that “the excitement attendant on the solution of the Battersea Mystery did not prevent Lord Peter from securing this rare work before his departure for Corsica.”

After Whose Body? Sayers ceased to supply these delectable footnotes on the editions acquired by Lord Peter, and indeed wrote much less about his bibliophilic activities, yet these never fade entirely from the series. In Unnatural Death (1927), for example, we catch a glimpse of fun: “Detaching his mind from crime, Lord Peter bent his intellectual and financial powers to outbidding and breaking a ring of dealers, an exercise very congenial to his mischievous spirit.” Evidently, at the time Sayers wrote this novel, auction bidding rings did not qualify as “crime” because they were still legal in the UK, but very soon thereafter, the Auction (Bidding Agreements) Acts of 1927 was passed, presumably in response to the sort of egregious behavior that Lord Peter witnessed.

The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928) begins with the Debrett’s entry for “Wimsey, Peter Death Bredon, D.S.O., born 1890,” in which we learn that Lord Peter is the author of Notes on the Collecting of Incunabula as well as The Murderer’s Vade Mecum and other works. Only one further notice of bibliophilic interest occurs in Unpleasantness, but it is a precious one, revealing that his collection is not limited to printed materials. “About ten days after that Armistice Day, Lord Peter was sitting in his library, reading a rare fourteenth-century manuscript of Justinian. It gave him particular pleasure, being embellished with a large number of drawings in sepia, extremely delicate in workmanship, and not always equally so in subject.” Sayers seems to have based all her descriptions of Peter’s books on real models, though I have been unable to track down a medieval copy of the Institutes (or other legal works attributed to Justinian) with sepia drawings. At Peter’s side as he reads is a decanter of “priceless old port,” presumably his favorite Cockburn 1908. My, my, what would a Special Collections librarian say? Would he scold Peter for imbibing liquids, even priceless ones, while reading priceless books? Or would he join his host in a jolly glass of the good stuff?

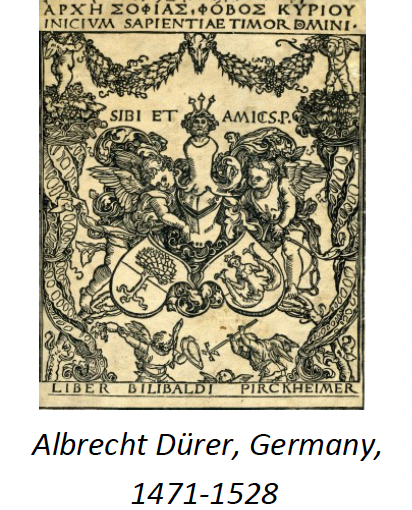

“The Learned Adventure of the Dragon’s Head” appears in the story collection Lord Peter Views the Body (1928). It is of particular interest because it shows Lord Peter introducing his young nephew Viscount St. George (affectionately known as “Gherkin”) to the pleasures of bibliophily. As the tale opens, our hero says to Mr. Ffolliott, the bookseller, “No, I don’t think I’ll take the Catullus…After all, thirteen guineas is a bit steep without either the title or the last folio, what? But you might send me round the Vitruvius and the Satyricon when they come in.” One wonders what Mr. Ffolliott was thinking, to offer his lordship an incomplete copy, lacking the title page no less! Peter happens to be saddled with ten-year old St. George for the day, and when little Jerry draws his uncle’s attention to a book with “funny” pictures in the doorside bargain bin, his expectations are low: “He prepared to receive Gherkins’s discovery with respect, though…the book might quite well be some horror of woolly mezzotints or an inferior modern reprint adorned with leprous electros.” Instead, enthralled by its depiction of the “Cracow monster,” a Polish infant purportedly born with a superfluity of dog’s heads attached to its body, Jerry has selected an imperfect copy of Munster’s Cosmographia Universalis, priced at 5 shillings. In this situation, the loose covers and missing maps do not signify, for the Gherkin has demonstrated a keen and precocious bibliophilic aptitude! When Jerry sees another woodcut of “a man chopped up in little bits,” he sets his heart on acquiring the book, and Uncle Peter allows him to purchase it from his pocket money. Thus is set in motion a delightful adventure involving a pirate, a sea-dragon, buried treasure—and marginalia.

In Strong Poison (1930), Adam in his Bibliophilic Garden catches sight of Eve, and we learn that it is no longer good for the Man to be Alone With His Books: “The stately volumes on his shelves, rank after rank of saint, historian, poet, philosopher, mocked his impotence. All that wisdom and all that beauty, and they could not show him how to save the woman he imperiously wanted from a sordid death by hanging.” When Lord Peter first meets Harriet Vane in the prison where she is held on suspicion of murder, he immediately proposes matrimony. By way of introducing himself, he explains that his wife needn’t bother with the “old oaks and the family plate” of the Wimseys. He collects “first editions and incunabula, which is a little tedious of me, but you wouldn’t need to bother with them either, unless you liked.” By “first editions” Peter presumably means firsts of canonical literature up through the Renaissance, but at one point in Strong Poison, he unexpectedly represents himself as a collector of modern first editions. Visiting Messrs. Grimsby & Cole, publishers of Harriet’s deceased lover Philip Boyes, he tries to obtain firsts of Boyes’s works, but is told that due to the notoriety of the murder case, a first London edition cannot be had “for love or money.” Instead Mr. Cole offers him “a special memorial edition, with portraits, on hand-made paper, limited and numbered, at a guinea,” and he readily agrees to subscribe.

The short-story collection Hangman’s Holiday (1933) contains a tale of particular delight for lovers of classical languages, “The Incredible Elopement of Lord Peter Wimsey.” In a remote village in the Pyrenées, the locals believe that the resident English doctor’s wife, who has sunk to a pitiful, mindless state, is bewitched by devilish powers. One day a Wizard appears in the village and rapidly gains a reputation for powerful (yet Christian) magic. He gains the trust of the local priest, who converses in Latin with him and delights in the sight of “a very handsome Testament with pictures in gold and colour.” The bewitched woman’s devout nurse is deeply impressed by such magical spells as Glaucus’s speech to Sarpedon in the twelfth book of the Iliad, delivered in the original Greek, plus a page or two of the sonorous Catalog of Ships from Book Two. (The former passage, I suspect, was carefully selected by Sayers, and bears on Peter’s experience in the trenches of WWI: “Ah friend, if once escaped from this battle we were for ever to be ageless and immortal, neither should I fight myself amid the foremost, nor should I send thee into battle where men win glory” [Tr. A. T. Murray, 1924]). Over the nurse’s humble offering of a bottle of wine, a silver penny and an oat cake, he murmurs the heavily spondaic “Ergo omnis longo solvit se Teucria luctu” (Aeneid 2.26, “Therefore was all Troy released from its long grief”). The Wizard solemnly hands the nurse a coffer containing the magical cure for her lady’s mortal ills, intoning “Tendebantque manus ripae ulterioris amore” (Aeneid 6.314, “And [the dead] stretched forth their hands with desire for the farther shore”). This performance is capped by a vigorous final incantation: “Poluphloisboio thalasses. Ne plus ultra. Valete. Plaudite.” Needless to say, the Wizard rescues the hapless lady from her devilish (and murderous) tormentor. The intriguing reference to Lord Peter’s elopement is of course a clever bit of misdirection, having nothing to do with Miss Vane.

Mr. Theodore Venables, Rector of Fenchurch St. Paul in The Nine Tailors (1934), is one of my favorite Sayers characters and Tailors, which explores the esoteric world of English change-ringing, is perhaps her finest novel. Dorothy Sayers’ father was Rector of the ancient parish of Bluntisham-cum-Earith in the Fens of East Anglia (which had its own set of bells), and no doubt there is much of Henry Sayers in Rector Venables, the gentle and absent-minded churchman who takes in Lord Peter and Bunter when the Daimler slides into a ditch on a snowy New Year’s Eve: “Lord Peter Wimsey—just so. Dear me! The name seems familiar. Have I not heard of it in connection with—Ah! I have it! Notes on the Collection of Incunabula, of course. A very scholarly little monograph, if I may say so. Yes. Dear me. It will be charming to exchange impressions with another book-collector. My library is, I fear, limited, but I have an edition of The Gospel of Nicodemus that may interest you.”

Gaudy Night (1936) is the book in which Lord Peter finally wins his Harriet after five years of rejection. Having retreated to her alma mater in Oxford in order to hide from herself, Harriet chances upon a non-fatal if nasty little mystery, and is tasked by the Shrewsbury College dons to sort it out. Eventually she yields to common sense and asks Peter to help, which he is only too glad to do, especially if it involves punting on the Isis with a picnic basket and long conversations with his beloved about life, the universe and everything. In the pocket of the slumbering Wimsey, Harriet finds a calf-bound copy of Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici (1642) with Peter’s armorial bookplate on the inside cover. “Did he fill in the spare moments of detection and diplomacy with musing upon the ‘strange and mystical” transmigrations of silkworms and the ‘legerdemain of changelings’?” she asks herself. Why ever not? Later we are treated to a list of Lord Peter’s favorite authors and works (to read, that is): Religio Medici, Kai Lung, Alice in Wonderland, Machiavelli, Boccaccio, the Bible, Apuleius, and last but not least, the metaphysical poet John Donne. Alice and Apuleius contribute touches of otherworldly magic and gentle but incisive humor, while Kai Lung turns out to be not a historical Chinese sage like Confucius or Sun Tzu, but a fictional sage and storyteller created by Ernest Bramah (1868-1942). Most of all, this Wimsical Library is notable for its blend of the spiritual and the earthy, the worldly and the transcendent.

In Busman’s Honeymoon (1937) which recounts the Vane-Wimsey nuptials and their aftermath, we hear more of Donne, for Harriet dispatches three stories to Thrill magazine in order to raise the 120 guineas for her wedding gift to Peter: an autograph letter by John Donne on Divine and human love. As the Dowager Duchess of Denver reveals in her diary entry for 4 October 1935, the bridegroom first “flushed up in the absurd way he has when anybody says anything rather personal to him, and stood staring at the thing till I got quite wound up.” The Duchess had been worried, for how was Harriet to find or afford a gift suitable for a very wealthy man of exquisite taste who could buy anything he wanted? Here’s how, in Lord Peter’s own words: “The funny thing is that the catalogue was sent to me in Rome, and I wired for this, and was ridiculously angry to learn it had been sold.” To complete the joyous ironic circle, he had wanted it for Harriet.

Two short stories set after the wedding, “The Haunted Policeman” (1936) and “Talboys” (1942) offer nothing further about Lord Peter’s bookish activities, and indeed suggest that some of the solitary adult pleasures of his old bibliophilic life inevitably gave way to the needs of a wife (however beloved) and three mischievous Wimsey boys. We hear of Peter issuing instructions for the library shelving of the new house in London, but Sayers left unwritten his no-doubt heartbreaking separation from the cozy library in his bachelor flat at 110A Piccadilly. The black baby grand piano and the books could be moved, of course, and the vases stocked with fresh chrysanthemums. Perhaps Talboys offered scope and shelves for a second library room to be filled with incunabula. But all good things do pass away, in time—except for Bunter, of course. Bunter is eternal.

6 thoughts on “Lord Peter Wimsey, Bibliophile”

Brava! I enjoyed your essay very much. It captures well Wimsey’s richness of character.

Many thanks for reading and for the feedback, Bob! So glad you enjoyed it.

Excellent essay. The use of illustrations enhances your text as well. Looks like it is time for me to read Sayers pronto. Keep writing, Jennifer! You’re already among the Classics.

Thanks Kurt! This was a fun assignment for me, re-reading them all with notebook in hand.

Jennifer,

I finally got around to reading your essay about Lord Peter’s bibliphilia. Well done.

As you know, I am an avid fan of Sherlock Holmes but sadly he was not a bibliophile. I wonder if Reid has copies of Lord Peter’s books? I believe he has the Sherlock Holmes book, The Art of Detection.

Thanks for reading, Dick! Yes, Reid has Lord Peter’s book on incunabula and at least one other. We will learn more in his upcoming exhibition! -Jennifer