By Richard Kopley

There are sweet spots in any book collection. In the midst of the highest shelf of my Hawthorne collection is a sweet spot so sweet that I sometimes visit just to see it.

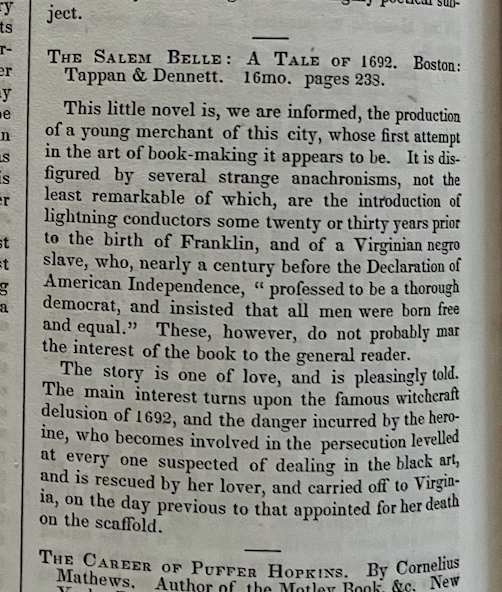

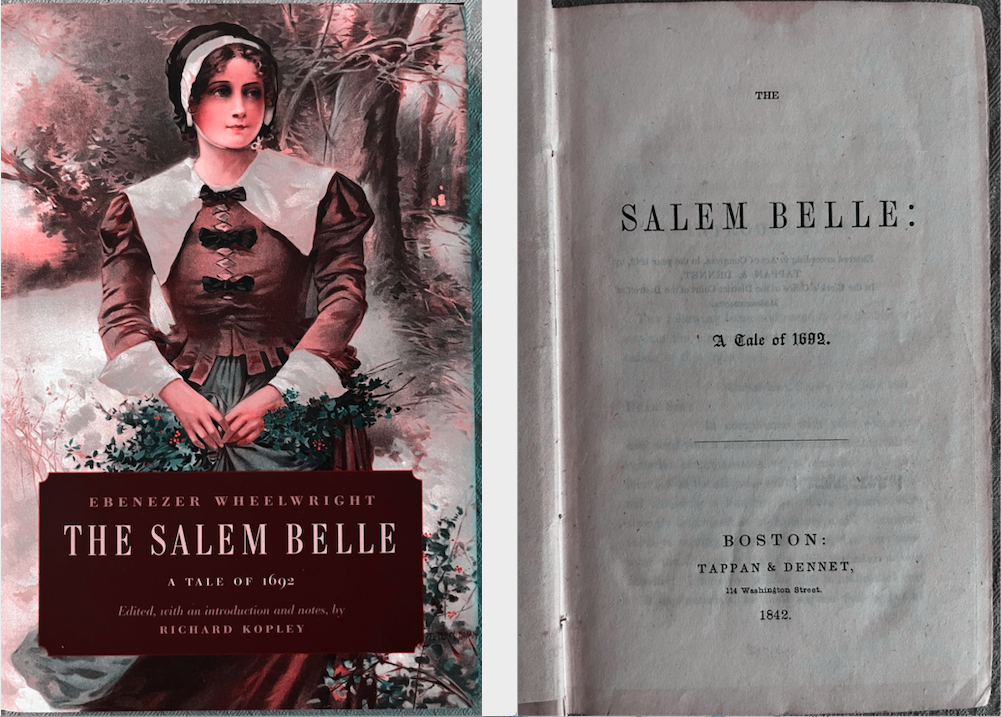

It took me two years to work out the author of the anonymous 1842 novel The Salem Belle: A Tale of 1692, published by Tappan and Dennet, of Boston. I was led to the book by my interest in Poe’s short story “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Having argued that that story had influenced chapter 10 (“The Leech and His Patient”) of Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, I decided to read carefully the January 1843 issue of The Pioneer, in which Poe’s tale first appeared. We know, from a letter from Hawthorne’s wife Sophia, that the Hawthornes had received the issue. A friend of editor James Russell Lowell and soon to be a contributor to the February and March issues, Hawthorne would doubtless have read that January issue. Of greatest interest there, after Poe’s tale, was a book review that mentions the rescue of the book’s heroine a day before her intended “death on the scaffold.” Well, of course, The Scarlet Letter ends with a death on the scaffold. And the focus on Salem and witchcraft in the reviewed book suggested the likelihood of Hawthorne’s interest—as did the book’s publication by Hawthorne’s publisher. So, relying on a microfilm copy at Pattee/Paterno Library at Penn State, I read The Salem Belle.

The book, set in 1692 Boston and Salem, concerns a rebuffed suitor’s false accusations of witchcraft against the woman he had courted. From the setting, detail, and language of three passages in the final third of the narrative—a forest passage, a harbor passage, and a scaffold passage—I concluded that Hawthorne had transformed these passages for Chapter 16 (“A Forest Walk”), Chapter 21 (“A New England Holiday”), and Chapter 23 (“The Revelation of the Scarlet Letter”) of The Scarlet Letter. My problem, then, became who had written the source book

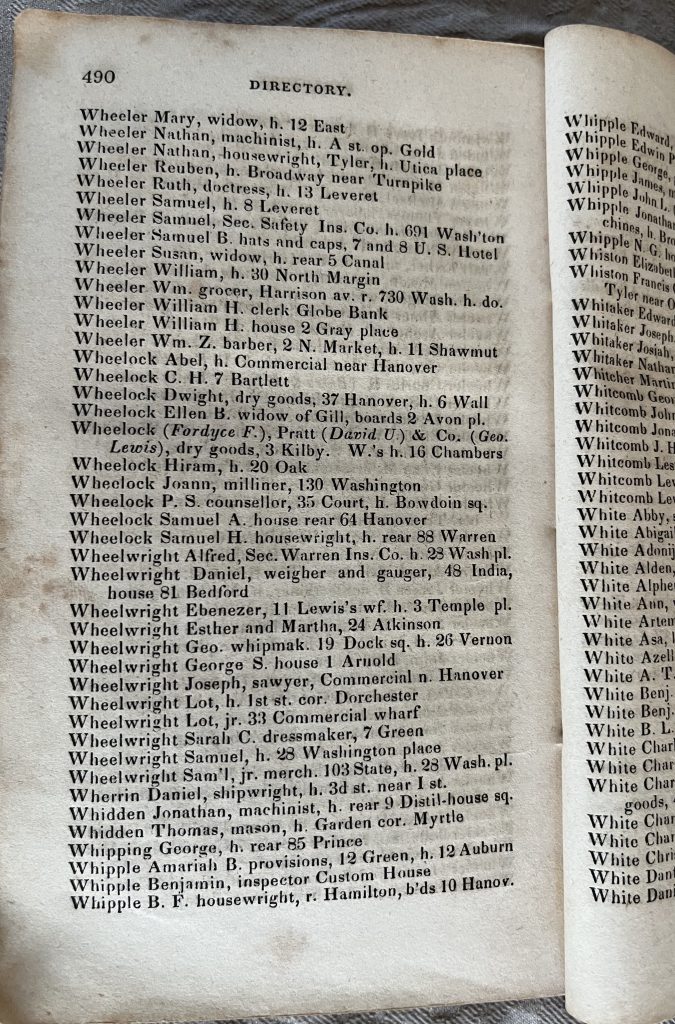

I queried librarians for markings in copies of The Salem Belle. The copy at the Lilly Library, signed by Jane Ann Reed, stated that the book was by Mr. Wheelwright. I consulted the Reed Family collection at Butler Library and discovered a letter by Jane Ann’s father Isaac about his reading the book and another by a friend to Jane Ann’s sister, asking if Mr. and Mr. Wheelwright still lived on Dover Street or if they’d moved. A check of Boston directories of the time showed that there was a Wheelwright who had lived on Dover Street and had moved to Temple Place, to the address of Charles Tappan: his first name was Ebenezer.

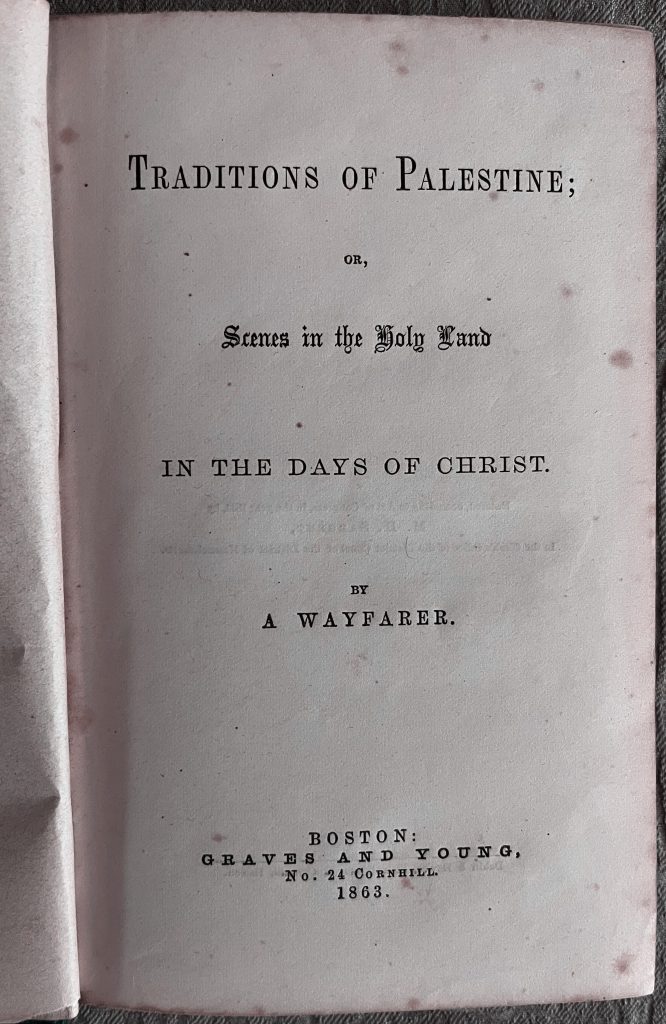

And so, the game was afoot. I recovered the story of Ebenezer Wheelwright Jr. through research at more than a dozen libraries, from Widener to the Huntington. Ebenezer was indeed the author of The Salem Belle—and of a novel anticipating Ben-Hur, Traditions of Palestine.

I wondered why Hawthorne had relied on Wheelwright’s novel, and, over time, I came to an answer. Hawthorne twice compares his heroine, Hester Prynne, to Anne Hutchinson, the woman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony who defied theocratic dogma about worldly evidence for salvation and asserted her inner sense of divinity. A student of Puritan history, Hawthorne would have known well that Anne Hutchinson had a partner in defying Governor Winthrop: John Wheelwright. A student, too, of Puritan genealogy, Hawthorne would have known that John Wheelwright was the ancestor of Ebenezer—the anonymous novelist’s great-great-great-great-grandfather. So, Hawthorne’s allusions to The Salem Belle were a cryptic allusion to the unknown author of that novel, the direct descendant of Anne Hutchinson’s partner in crime. Hawthorne had intimated both figures who had prompted the Antinomian Controversy.

And the historical allegory contains a biblical one. Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright disobeyed authority and were expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Where else have we read this story? Of course, it’s in Genesis, where Adam and Eve defy God and are expelled from the Garden of Eden. Hawthorne even refers explicitly in The Scarlet Letter to Eden “after the world’s first parents were driven out.” Throughout his career, Hawthorne meditated on the Fall and its consequences. And he did so in The Scarlet Letter through allusions to The Salem Belle

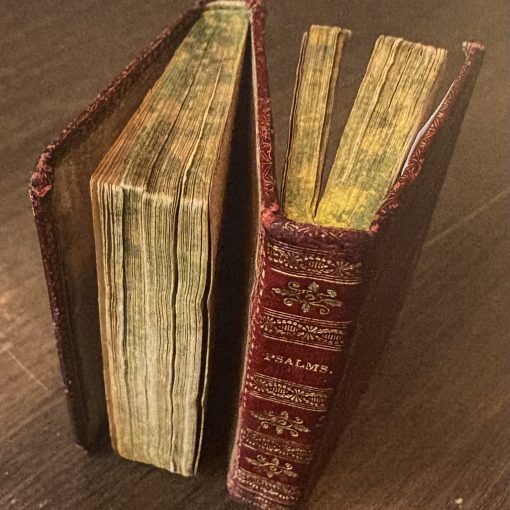

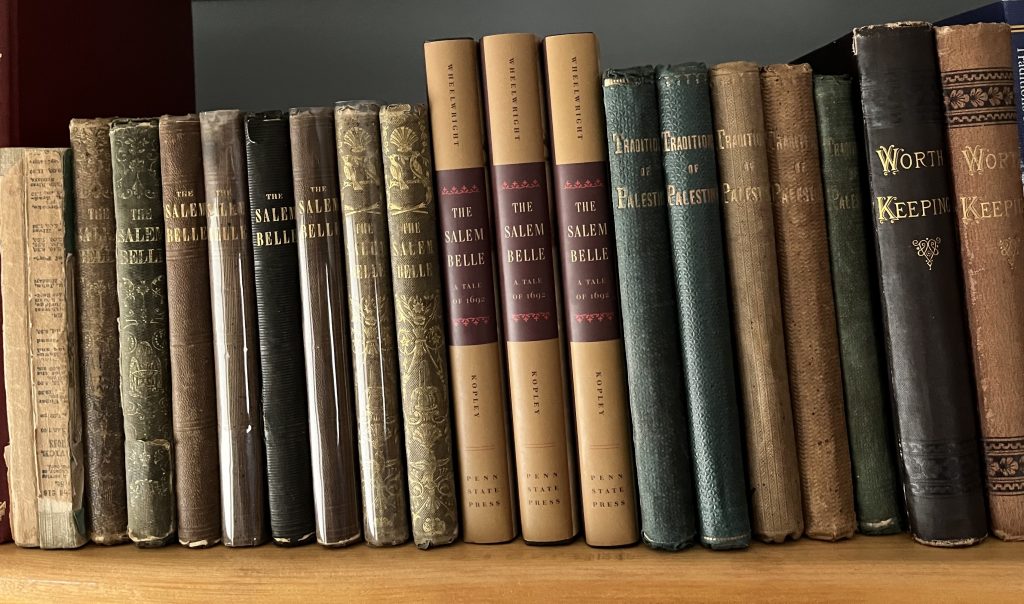

So I return to the sweet spot in my book collection. I see six copies of the first edition of The Salem Belle—all duodecimos, with original cloth boards (black, brown, or green and two designs). Most are in very good or fine condition, the titles on the spines easily legible. Next to these volumes are two copies of the 1847 John M. Whittemore edition, The Salem Belle: A Tale of Love and Witchcraft in the Year 1692. Also 12mos, they have especially attractive ornate spines. Next to these are three copies of my edition of The Salem Belle, published by Penn State Press in 2016. For the first time, Ebenezer’s name appears on his book—as does my own. And beside these appear five copies of Ebenezer’s novel Traditions of Palestine—four of these the 1863 Graves and Young edition, and one of them the 1864 M. H. Sargent edition. Again the volumes are mostly very good or fine.

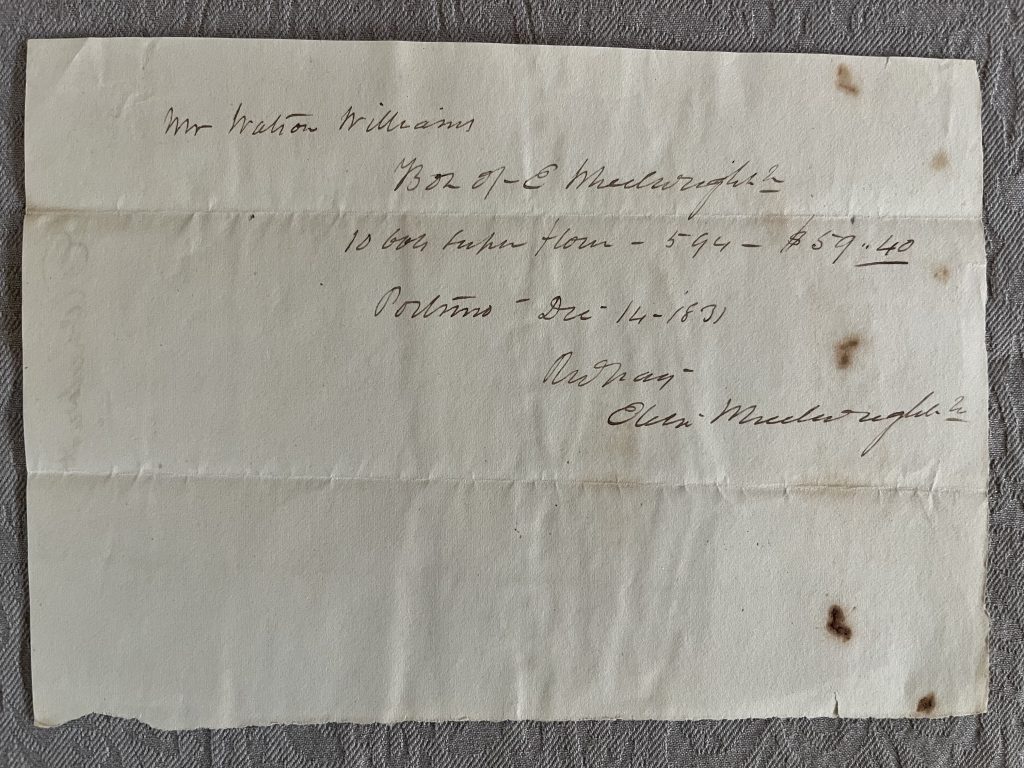

Among my other Wheelwrightiana in this sweet spot are a copy of the Boston directory of 1842, with “Wheelwright Ebenezer” listed at 3 Temple Place, and two copies of the 1880 Worth Keeping: Selected from The Congregationalist and Boston Recorder, 1870-1879, with a posthumous attribution of a piece to “Eben Wheelwright.” Looking over all these books, I thrill to see that he who was so long unknown is now not only known, but also, in my collection, abundantly present. And when my eyes have had their fill of my Wheelwright volumes, I turn to a blue loose-leaf notebook, resting on the desk. I find there five receipts for flour, written in the 1830s, all signed by a Portsmouth flour merchant: “Eben Wheelwright Jr.”

Richard Kopley is Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus, at Penn State DuBois. Former president of the Poe Studies Association and the Nathaniel Hawthorne Society, he is the author of Edgar Allan Poe and the Dupin Mysteries, The Formal Center in Literature: Explorations from Poe to the Present, and The Threads of The Scarlet Letter. He is also the editor of Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and Ebenezer Wheelwright’s The Salem Belle. Recipient of the Poe Studies Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, Kopley is completing a biography of Poe. His collecting interests reflect his scholarly work—he focuses primarily on Poe and Hawthorne. He is a member of The Grolier Club and The Ticknor Society.