By Marcia McBrien

How and where readers buy books – and how they bought reading material in the past – is a question “just as serious as it is fun,” said Paul J. Erickson, director of the Clements Library at the University of Michigan.

Speaking to the Book Club of Detroit at the Club’s annual holiday luncheon, Erickson commented that “Where we buy shapes what we buy. So, for example, if you only bought books in an airport, you’d end up reading a very different body of literature than if you only bought books at Target, or at a campus bookstore, or at a local independent bookshop.”

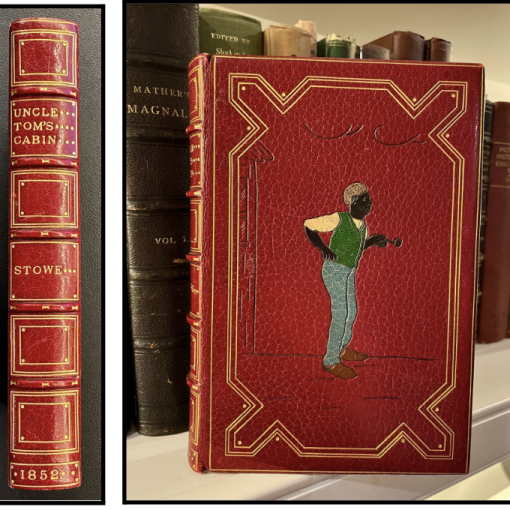

Those choices matter because, Erickson noted, “books have the power to shape what we think.” And the recognition that “books are different than shoes or pickles” is the basis for what most book lovers think of as a bookstore – a beloved place of easy-to-browse bookshelves, chairs for reading, and expert staff. Indeed, “There are no businesses about which contemporary American consumers are more sentimental than bookstores,” Erickson told the BCD audience.

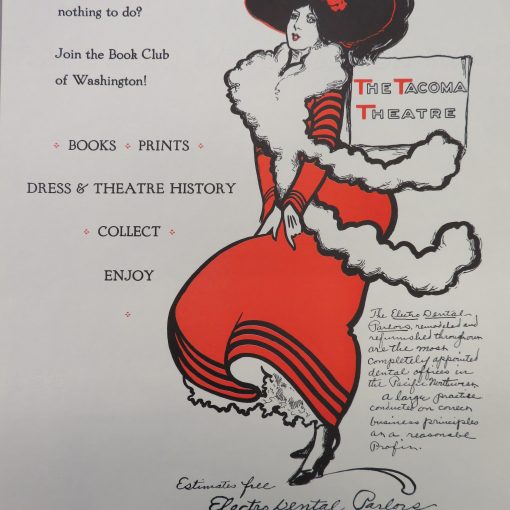

But while many assume that this “Platonic ideal” has always been the standard for book selling, in fact, most 18th and 19th Century Americans would never have set foot in a “books-only retail outlet,” Erickson explained, because most Americans did not live in large cities. Those living in small towns or rural areas bought books, magazines, and other reading material by mail, from itinerant book peddlers, or at general stores offering a “promiscuous assortment of all types of goods, more like a condensed version of Target than an independent bookstore.” Even in cities, stand-alone booksellers were rare, with most buying their reading material from newsstands, street vendors, or department stores.

And even reputed booksellers were often in other lines of business, Erickson noted. An 1899 list of the 10 “leading book dealers” in Columbus included three hotel newsstands (which also sold cigars), a train station newsstand, a “one-armed barber,” and a seller who after a year and a half turned to selling produce.

In the late 1890s, the book trade, spurred by competition from other retailers, worked to define “what made a bookstore a bookstore” and to distinguish bookselling as a profession whose goal was educating the community. An 1875 guidebook to Cincinnati called the George E. Stevens Bookstore “a resort for lovers of books,” where customers could browse without feeling pressured to buy. Advocates like bibliographer Adolph Growel, who worked for Publishers Weekly, urged booksellers to stock a wide variety of books, to make their shelves accessible for browsing, and to engage in “much reading and study” so as to guide their customers. In contrast to other merchants, the bookseller should be “an educator and a blessing to any community,” Growel advised. This vision of the “ideal bookshop” promoted by late-century booksellers “bears the closest resemblance to our contemporary local independent bookstore,” Erickson said.

So, Erickson asked, “What makes a bookstore a bookstore?” As in the past, bookstores defy neat categories. Our belief that “books are special” can direct how and where we buy our books – and what we derive from the experience.

About Paul Erickson and the Clements Library

Paul Erickson is the Randolph G. Adams Director of the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan. A native of Minnesota, he earned a B.A. in English from the University of Chicago and an M.A. and Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. His work experience spans the publishing, nonprofit, and special collections worlds. From 2007 to 2016, he served as Director of Academic Programs at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts; from 2016 to 2019, he was Program Director for Humanities, Arts & Culture and American Institutions, Society & the Public Good at the American Academy of Arts & Sciences at Cambridge, Massachusetts. He has written and lectured widely on, among other topics, antebellum urban fiction, print culture, the history of the book, and the role of research libraries in the digital age. He joined the Clements Library in January 2020.

The Clements Library, founded in 1923, houses original resources for the study of American history and culture from the 15th through the 19th centuries. Its mission is to collect and preserve primary source materials, to make them available for research, and to support and encourage scholarly investigation of our nation’s past.

Marcia McBrien is President of The Book Club of Detroit.

One thought on ““What Is a Bookstore?”: Bookselling in the 19th Century”