by Joshua Shelly

Editor’s note: Joshua Shelly (Ph.D. Duke 2023) won Second Prize in the 2023 National Collegiate Book Collecting Contest co-sponsored by the ABAA, FABS, the Grolier Club and the Rare Books division of the Library of Congress. We are pleased to share Dr. Shelly’s description of his collection.

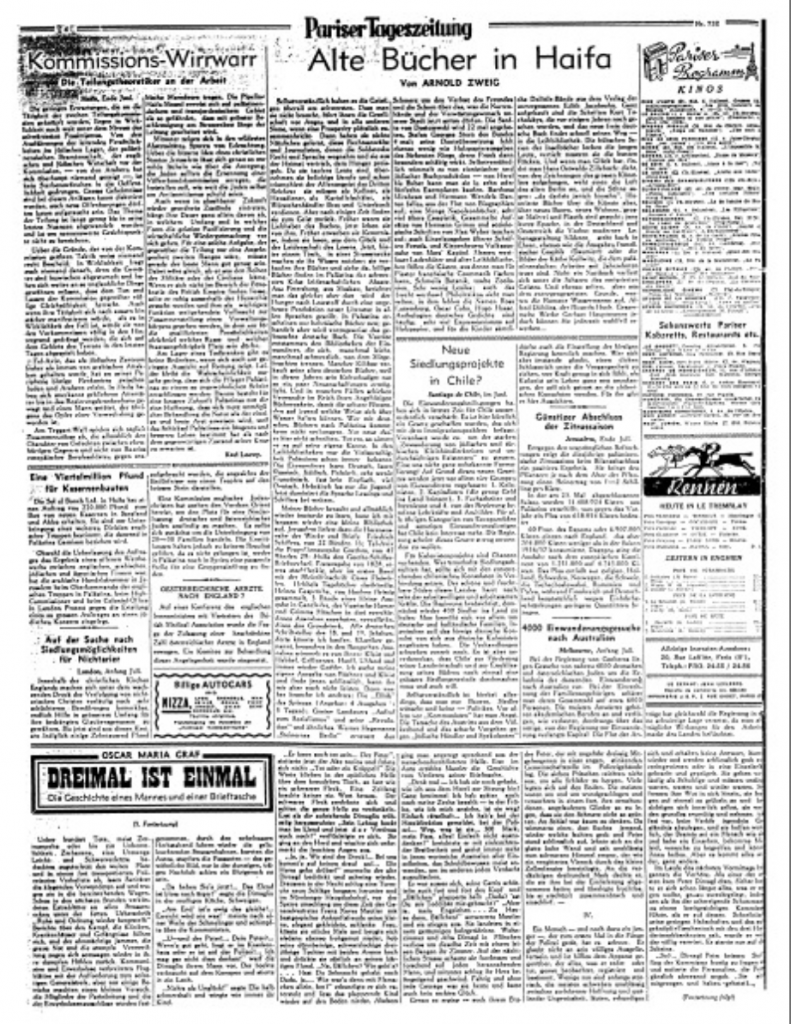

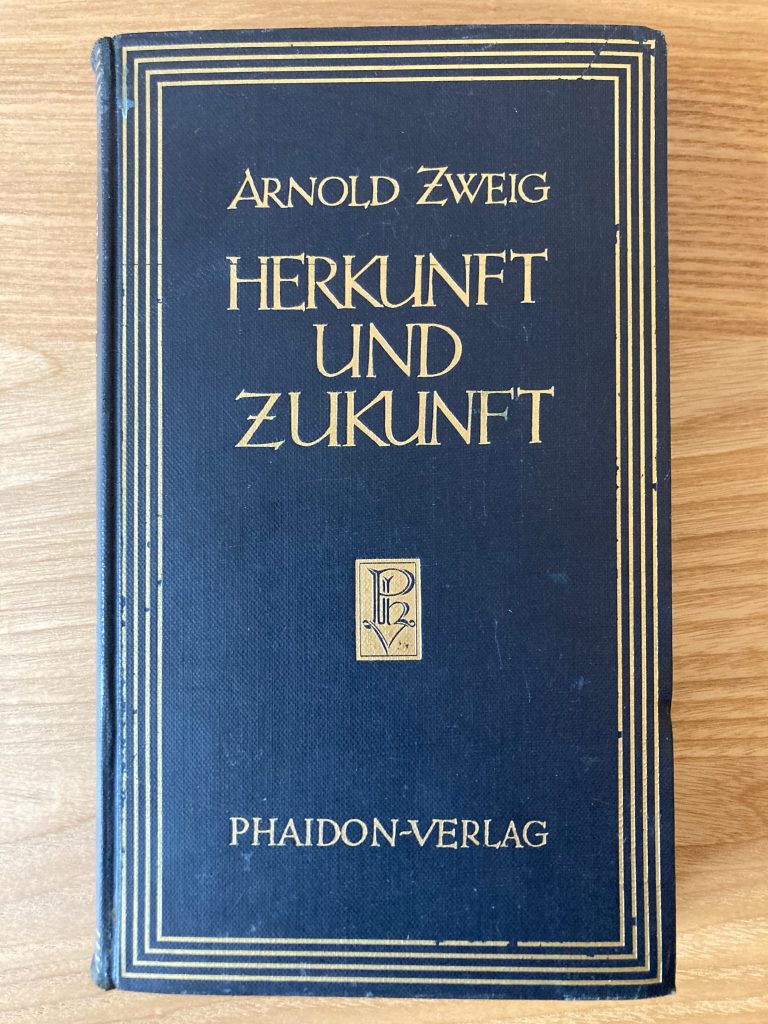

Several years ago, while working in the archives conducting research for my dissertation, I came across a draft of a short essay entitled “Alte Bücher in Haifa” (Old Books in Haifa).1 The text, published in 1938 in the German-language exile press, was written in Palestine and details the experience of its author, Arnold Zweig, as he searches for German books in a city where only Hebrew works are published.

Zweig, whose considerable library had been seized by the National Socialists during his flight from Germany several years earlier, was reliant on the city’s used-book market to reconstruct his collection. The titles he lists in the essay range from the complete works of giants of German literature such as Goethe and Schiller to (then) more recent fare by Theodor Herzl and Martin Buber. For me, the draft’s three short pages evoked a generation of Jews that continued to seek solace in the pages of German literature, even while its members packed their bags and set sail for far-off locales in search of refuge.

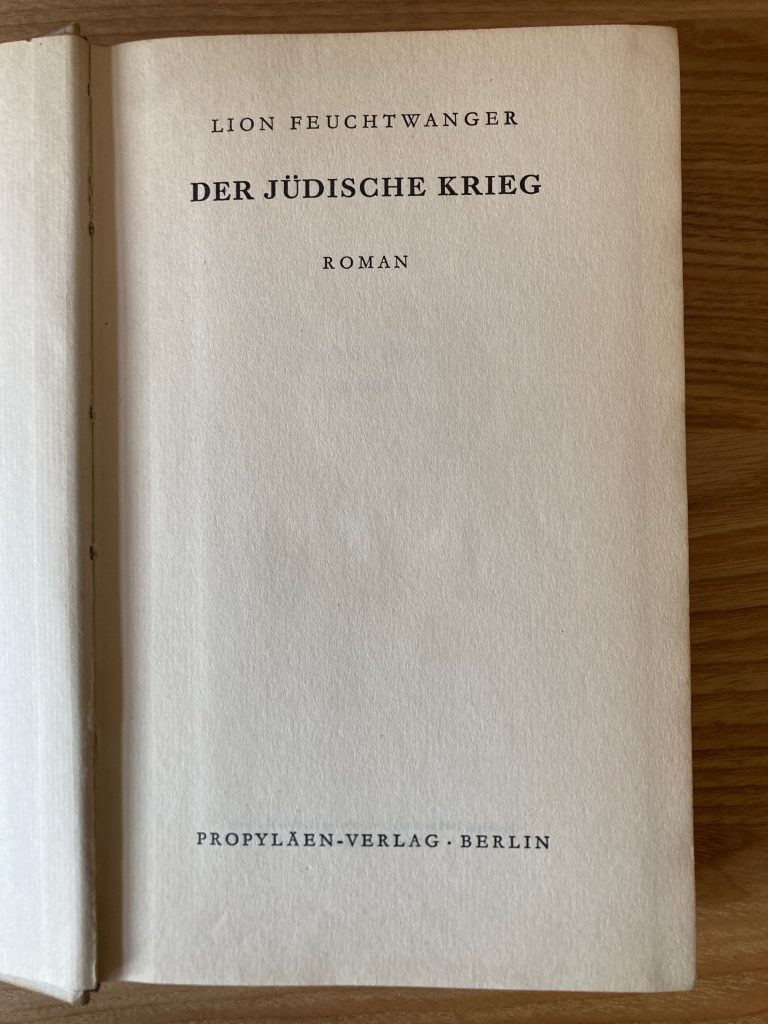

I build my own library more than eighty years removed from Zweig, yet his essay is not disconnected from my own acquisitive impulse. My collection of books, all important to German Jews in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, is related to my research on German Zionist literature but also reflects a broader affection for, and interest in, works that extend far beyond the narrow confines of this topic. Whether clicking through internet pages on the path to that one title, browsing Bücherschränke (little libraries) near my home in Berlin, or else leafing through physical pages in a book shop in Jerusalem, my decision to add a book to my collection is shaped by factors such as the object’s physical condition, price (where relevant), and my own idiosyncratic literary taste.

One of the unique aspects of German Jewish literature is the wide range of places one can locate titles. In the course of the Shoah (Holocaust), European Jews fled to places as disparate as Palestine, the United States, central Asia and even Shanghai, China. In flight, they brought not only passports and clothes, but also precious titles from their libraries. And this is not without consequence. For the book collector like me, this means that titles of interest are just as likely to be found in used book shops in New York or Tel Aviv as in Berlin or Frankfurt. Indeed, as Tom Segev notes, many classics of German literature “survived only in Palestine since the Nazis had confiscated and burned all the copies in Germany.”2

I thought about this a few years ago when I was in Israel on a research fellowship. On the recommendation of one of my colleagues at the Hebrew University, I found my way to Pollak Books in Tel Aviv, a store bursting at the seams with German books piled two, three, even four layers deep. Overwhelmed by the number of volumes before me, I set to work sifting through what I could in my limited time there. Paging through various volumes, I thought of the “Yekkes” — German Jews — who brought these books with them during their emigration. Many left whole libraries behind to sons and daughters who could no longer read their contents. At another bookstore in Jerusalem, I came across an unorganized carton of German books. The store owner, indicating the box, laconically noted that it had been left on his door step. I wondered who sought to offload these books and what journey they had undertaken to end up in a pile before me.

My collection might best be described as consisting of works published in German that were of interest to at least one segment of the German-reading Jewish public during the latter part of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. Of course, this community was interested in a wide variety of titles, but I limit myself to those works that thematize questions of Jewishness and/or depict Jewish characters. Although almost all the books I own are versions of the works published during this same time period, I sometimes allow myself liberties for texts republished at a later date or those only made available in their full form after the Second World War. In assembling this collection, I view myself as performing an act of remembrance, creating a little monument to a community often associated with tragedy, but that also ought to be remembered for the dynamic cultural treasures they read and produced and whose stories continue to live on in the pages of volumes that sit on my bookshelves today.

1Arnold Zweig, “Alte Bücher in Haifa” in Pariser Tageszeitung 3, no. 732 (July 8, 1938).

2Tom Segev, The Seventh Million, translated by Haim Watzmann (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000), 47.