by Jennifer Larson

Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray. 2021. The Personal Librarian. New York: Random House.

Heidi Ardizzone. 2007. An Illuminated Life: Belle da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege. New York: W. W. Norton and Co.

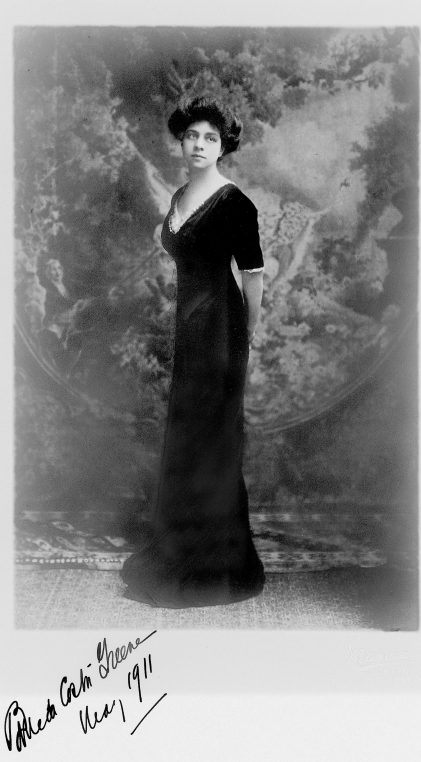

In The Personal Librarian, authors Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray aim to portray J. P. Morgan’s librarian Belle da Costa Greene as an inspiring heroine and role model, a woman who overcame the challenges of the deeply racist and sexist culture that surrounded her in early twentieth-century America. Indeed, Greene deserves much more attention and praise than she has received to date. The book succeeds in showing just how daunting these challenges were, and how Greene, who chose to live as a white woman, may have been haunted her entire life by the possibility that her African-American ancestry would be exposed.

I have two criticisms of the book. First, in the service of depicting a salutary role model, Greene’s life is sanitized of behaviors that might draw disapproval, and the force of her magnetic personality is blunted. The real Greene was extroverted, brilliant and opinionated, to all appearances a self-confident Olympic-level flirt with an insatiable appetite for attention. The fictional Greene created by Benedict and Murray is earnest, constantly anxious and only mildly flirtatious; her flamboyant moments arise from a desire to “hide in plain sight.” She reflects today’s middle class values and gender expectations, despite abundant evidence that Greene herself rejected these in favor of a more bohemian life free of the suffocating social and sexual restraints of the period.

Greene’s very active sex life (which picked up considerably after the death of her jealous employer) is barely acknowledged in the novel—and her female lovers not at all. The many nude portraits of herself, which she kept in her bedroom and sometimes showed off to visitors, go unmentioned. In 1913, Belle wrote that she admired the kind of woman “who takes her pleasures as a man does and wearies of them and throws them aside as a man does…who has no morals but a sense of decency…” Even during the years in Morgan’s employ, she stayed out late every night, smoked, drank heavily and drove fast cars, all unconventional behaviors in an unmarried woman.

The Personal Librarian misses an opportunity to show how Belle interacted with her wild and scintillating late-night crowd, which included Isadora Duncan, Ellen Terry, Sarah Bernhardt, opera singer Mary Garden (she of the Dance of the Seven Veils), and many other creatives. Alfred Stieglitz is briefly described introducing Belle to the work of Matisse and Rodin, but her involvement in New York’s avant-garde circles is downplayed. Likewise we don’t see her acerbic wit, as when she wrote in 1924 to her boss Jack Morgan, “In regard to the Tennyson items, which personally I loathe, it is a question of perfecting your already very large and fine collection of imbecilities.”*

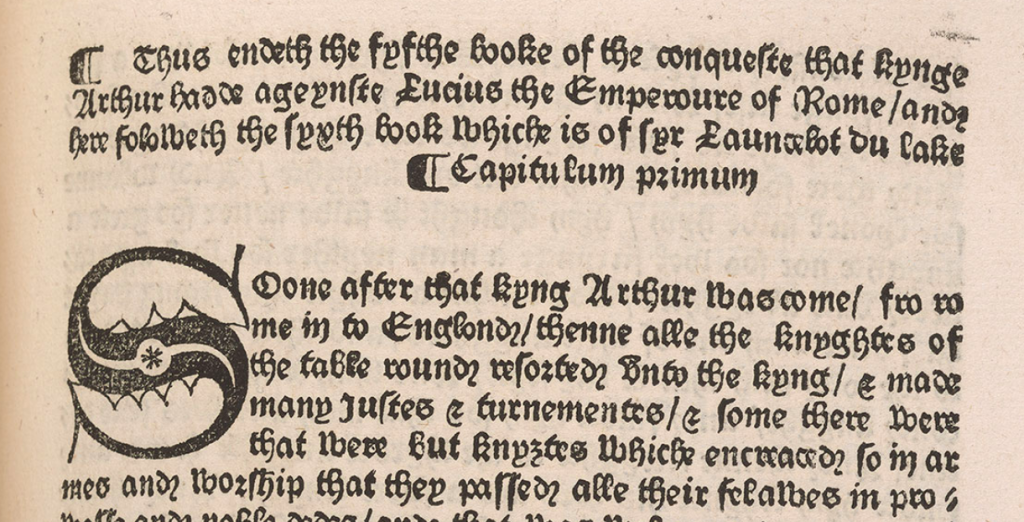

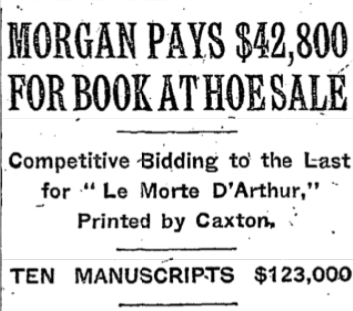

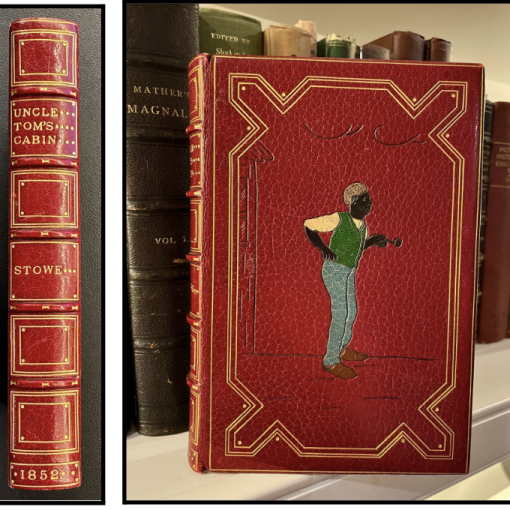

My second criticism is that The Personal Librarian will disappoint bibliophilic readers. Greene’s bookish passion and rich knowledge take a distant second or third place to the conflicts generated by her choice to live as a white woman and the depictions of her personal relationships. The most successful passages in the book are those that describe Greene interacting with her family members: their shared pride in their achievements as well as their shared struggles, their frustration at the ground lost to segregation and lynchings after the failed promise of Reconstruction, and the pain of permanent separation from Belle’s father after her mother and siblings changed their name to Greene and began to live as white people. Less successful are the descriptions of the books she purchased and curated, which are kept safely to the superficial lest they bore the non-bibliophile reader. We hear often of the Gutenberg Bibles and Morgan’s notable cache of Caxtons, but little of the rest of the collection. A few of Belle’s triumphs are briefly described: a 1638 King Charles I Bible in a red velvet binding purchased at the Wilkinson sale, the sixteen Caxtons acquired from Lord Amherst of Hackney in 1908, and the Caxton Morte D’Arthur purchased at the Hoe sale in 1911. Benedict and Murray describe the Hoe sale as if Henry Huntington were present and bidding for himself against Belle, whereas the New York Times reported that Huntington’s agent George D. Smith was her opponent (and thought to be bidding for himself on the Morte D’Arthur).

Despite these drawbacks, the book is worth a read because its dramatization of Greene’s life makes clear the cost of her achievement in ways that a non-fiction study cannot. It offers a plausible reconstruction of her relationship with J. P. Morgan (by turns filial and lover-like in ways sometimes disturbing). The depiction of her long-term affair with art historian Bernard Berenson is somewhat less successful, as the authors fail to show how Greene was also drawn to Bernard’s wife Mary. Their love triangle was tortured, tangled and long-lasting, even if much of it was conducted through letters.

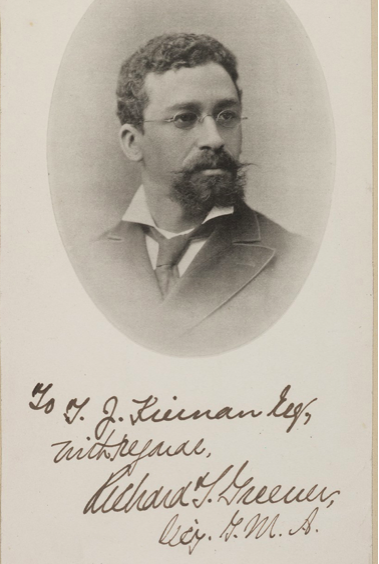

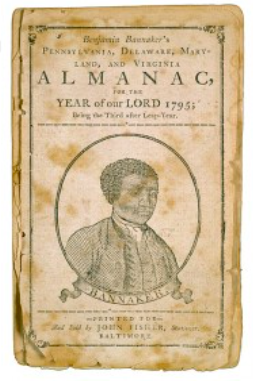

The Personal Librarian depicts the young Belle discussing Renaissance art with her father, and receiving Berenson’s 1894 book The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance from him (in real life it was inscribed from her Aunt Julia). Still, the brilliant Richard Greener may well have been the source of Belle’s passion for books. Richard Greener was the only member of the family who did not renounce his Black identity. The first African-American graduate of Harvard and the first Black faculty member at the newly integrated University of South Carolina, he taught Greek, Latin, math, philosophy, and logic while organizing the university library. According to Sarah Richardson, “he was so avid a book lover that he assembled a personal collection of African-Americana, including a copy of [Black mathematician and astronomer] Benjamin Banneker’s 1792 Almanac.”

Greener submitted an 1876 paper on ‘Rare and Curious Books’ in the USC library to the American Philological Association, of which he was a member. After the Supreme Court invalidated the 1875 Civil Rights Act and he was forced to resign from USC, Greener became Dean of Howard University’s law school and US Consul in Russia under President McKinley. Belle da Costa Greene was herself a collector who bequeathed her Persian, Turkish, Mughal and Arabic miniatures to the Morgan.

Heidi Ardizzone’s 2007 biography An Illuminated Life: Belle da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege was an important source for Benedict and Murray’s novel. Unfortunately, it now appears to be out of print, evidence (if any were needed) that Greene’s achievement and cultural significance has been insufficiently recognized. After failing to locate a copy on Biblio or AbeBooks, I grudgingly settled for the Kindle version (it is also available as an audiobook). While Ardizzone also gives relatively short shrift to the bibliophilic aspects of Belle’s career, she has more to say, and says it more accurately, than Benedict and Murray.

Ardizzone discusses Greene’s friendships with Alfred Pollard, expert on incunabula and head of rare books at the British Museum; Charles Hercules Read, the Keeper of British Antiquities who began the Museum’s publication program; Sydney Cockerell (not the bookbinder), Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge; manuscript collector Henry Yates Thompson; Charles Freer, who introduced Greene to Chinese art, and many others. The Morgan Library’s 1911 purchase of more than fifty ancient Coptic biblical manuscripts from the Fayum is discussed in detail, as is Greene’s long and intimate friendship with Père Henri Hyvernat, the Copticist engaged to study and publish the manuscripts. One of Belle’s particular favorites was Harry Widener, a discerning young collector who loved to spend time in the Morgan Library. When he perished in the sinking of the Titanic, she wrote to Berenson, “My heart almost breaks when I think of dear little Harry Widener…It is the most shocking thing that has happened in my day.” (Harry’s mother, who survived the disaster, went on to donate the Widener Memorial Library at Harvard in his memory.)

Greene had low points as well as high, including at least one episode of shockingly poor judgment. In the Feb 1925 issue of The Bookman, Edward Larocque Tinker reported that Greene told him she had destroyed several of George Washington’s letters because they were “smutty” and she feared that they would tarnish “the ideal of Washington.” If true, the story displays overweening confidence in her own judgment, and a sense of ownership of the collection that came from her long tenure at the library. Sadly, Belle also destroyed her personal papers toward the end of her life, perhaps fearing that her own image would be damaged if they were found to be “smutty.” Fortunately, Mary Berenson saved a cache of hundreds of Belle’s letters to Bernard, which Ardizzone used extensively in her biography. When published, these will surely reveal much more of interest to the bibliophilic reader.

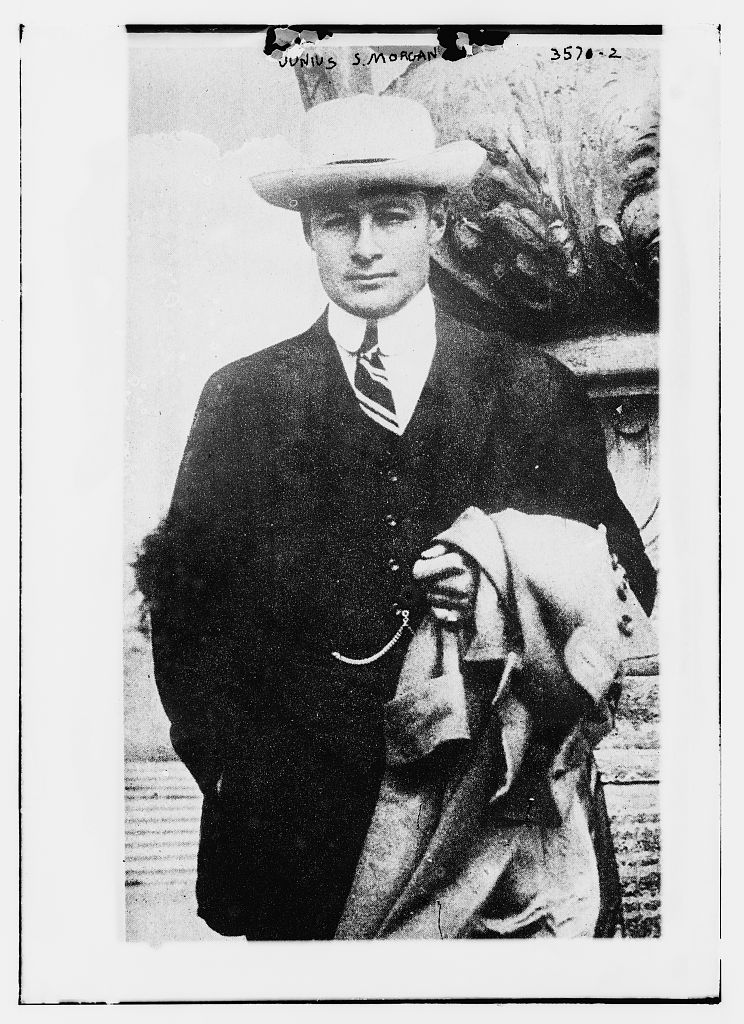

Ardizzone also explores the interesting question of Greene’s preparation for the librarian job, a matter that Benedict and Murray mostly leave to the reader’s imagination. Before coming to the Morgan Library, Greene’s professional training consisted of a summer bibliography course at Amherst and three years in the Princeton library, where she worked under Ernest Richardson, a pioneer in cataloging and a teacher of bibliography and paleography. Her other key influence during this period was Associate Librarian Junius Morgan, J.P.’s bibliophilic nephew, who guided his uncle’s early book purchases.

A Grolier Club member (as was J.P.), Junius assembled a collection of early printed editions of Vergil, which he later donated to the Princeton Library. Ardizzone speculates that Junius proposed Greene for the librarian’s job because he wanted to continue guiding the development of his uncle’s collection. It is likely that Greene turned to Junius for advice often in the early years. But Belle da Costa Greene’s success is attributable to her own brilliance, hard work and intellectual engagement with the materials in the collection. She learned on the job, taking lessons in Italian and German, and sharpening her skills in French and Latin. Her assistant, Ada “Thursty” Thurston, had more training in cataloging than she did, but it was Belle who negotiated prices with booksellers, and Belle whose taste and judgment influenced her wealthy employers. Most importantly, it was Belle who thought big, convincing J.P. and later his son Jack to let her build a collection that rivaled the greatest in the world, and ultimately (1924) to transform it into an institution that served the public. We are all the richer for her work.

POSTSCRIPT: A new novel about Belle da Costa Greene by Alexandra Lapierre was published in French by Flammarion in 2021. An English translation is expected in June 2022.

8 thoughts on “In Search of the Bibliophile’s Belle da Costa Greene”

Jennifer, thanks for these fine reviews. Neither of these works does Belle Greene justice in regards to her primary occupation / focus as a rare book hunter. The meat and meaning of her life involved being immersed in the world of rare books, not what color she was or her active night life. A biography / lengthy essay of her written by someone familiar with the rare book world has great possibilities. Between the transcribed Berenson correspondence and the Morgan Library archives it should now be possible. Hmmm…..

Thanks for the comment, Kurt! I have just received the novel in French about Greene and on first glance it seems similar in coverage to “The Personal Librarian.” I agree with you that the Berenson correspondence and the Morgan archives could offer materials for a much more focused look at the bibliophilic aspects of her life, which after all were the most important to Greene herself.

Thank you, Jennifer, for this fascinating article and for leading me down another interesting rabbit hole. Your reference to Greener’s papers found in an old steamer trunk in an attic intrigued me. Tim Lacy wrote about it for the Society of U.S. Intellectual History in the January 23, 2014 issue. Don’t we all dream of such a find?

Many thanks for the reference, Charlene! Yes indeed, and I feel sure that more fascinating discoveries are waiting out there in storage units and (more romantically) in attics. All that’s needed is the right pair of eyes to see their historical value.

This review points out many of the shortcomings of the fictionalized biographies of Greene’s life. Greene’s professional accomplishments are lost among Benedict/Murray and Lapierre’s focus on the risks of passing. Belle Greene’s voice is all but lost in Lapierre’s sensationalizing novel takes the focus on passing even further. Another oddity: her book translates Belle’s letters to Berenson from the original French edition of the book. I’ve reviewed this for Speculum. Greene made passing flippant remarks to the darkness of her skin but she never disclosed her ancestry.

Thank you for the comment, Deborah. One thing I’m certain of is that we need to know more about Belle Greene’s scholarly and curatorial work, which was, after all, at the center of her life.

New and used copies of Heidi Ardizzone’s book about Belle da Costa Green are available on Amazon.

Thanks for the tip, Kristine.