Reviewed by Jennifer Larson

Zinman, Michael. 2025. The Critical Mess. Annals of Collecting no. 10. New Jersey: Privately printed for the author. Distributed by Temporary Culture.

This compendium of essays by and about Michael Zinman is itself a “critical mess” as defined by the author:

“My approach to collecting was to accumulate as much material on a subject as possible, not worrying about condition or completeness, and after a critical mass was assembled, to sort it out and dispose of what I was done with.”

“If you have enough stuff, good and not so good, you see things that someone collecting only fine copies will miss.”

By searching out the defective items squirreled away in sellers’ basements, canny acquisition of costly items when they became available, and valuing ephemera as much as he did books, Zinman did what many had supposed impossible in the twentieth century. He formed a collection of early American imprints of such great historical value that it now resides at The Library Company in Philadelphia. William S. Reese, a longtime friend of Zinman’s, describes this feat in a talk (2000) included in this book.

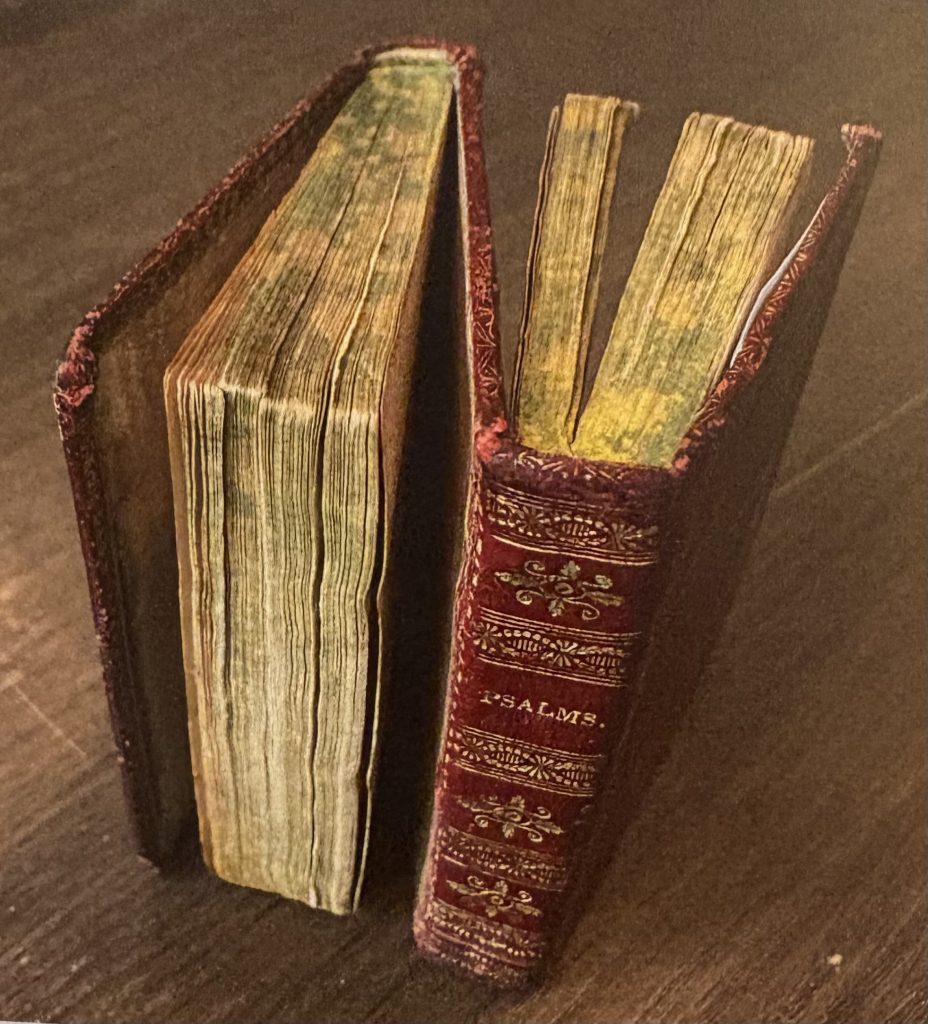

Above: a rare 19th-century American dos-à-dos binding from Zinman’s collection, and The Critical Mess by Michael Zinman with contributions from William S. Reese, James Green, Nicholas Basbanes, Rachel D’Agostino and Mark Singer.

The volume chronicles several other Zinmanian exploits, such as his assembly of 22 pre-1760 Bay Psalm Book editions, his collecting of printing for the blind, his acquisition of thousands of pamphlets microfilmed and dumped by the NYPL, which yielded a collection of constitutions of American social clubs and institutions, and of course his memorable endowment of urinals in the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library of the University of Pennsylvania, for which he commissioned poems from the various states’ poets laureate. (Several laureates enthusiastically participated, supplying “Quartet for Four Urinals & Flushing Mechanism,” “The Iambic Urinal,” “The Stream of Life,” “Urinary Tract,” and more. The poems alone are worth the price of the book.)

This is not a connected narrative, but rather a gathering of introductions, profiles, notes, odds and ends. There are anecdotes such as the story of “Lawrence’s flag,” a British-designed flag used by T. E. Lawrence in the Arab Revolt and saved by a sheikh who passed it on to a British officer. When this went to auction, Zinman wanted the headline to read “Property of a Jew,” but Sotheby’s declined the suggestion. He acquired an American Civil War diary full of memories of Gettysburg, authored by a soldier who was nowhere near Gettysburg on the date of the battle (apparently such diaries and memoirs are as common as big fish stories). And then there’s Zinman’s collection of “Tart cards,” pictorial cards offering the services of prostitutes, which used to be affixed to kiosks in London and other big cities.

When one has read the entire book, one feels that the critical mess offers insights into this unusual character, surely one of the most original thinkers in modern collecting. It reveals his impish wit, his contrarian instincts, and his generosity (he often gives rather than sells). Of his many collections there are two about which I would have liked to learn more. First, the bizarre titles collection MUST be catalogued. The full list of titles (e.g. Pamphlets by an Ass, How to Be Happy Though Married, The Cult of the Goldfish, Colon Cleanse the Easy Way!) would have made a delightful addition to this volume. Second, I would like to know more about the collection of American panhandlers’ signs (briefly mentioned in Mark Singer’s New Yorker profile “The Book Eater,” included in this volume). Such a collection, if large enough, would almost certainly illustrate the critical mess theory once again, telling us much about America in the late 20th and early 21st century—a turning point for worsening social and economic inequality.

What most interests me is how Zinman’s critical mess theory relates to the larger world of collecting and the impulses of collectors. The “accept damaged copies” aspect of the theory strongly contradicts the traditional, gentlemanly forms of collecting in which well-preserved copies with prestigious provenance were sought out as trophies, sophisticated as necessary, re-clothed in fancy bindings deemed more suitable to the valuable contents, and so forth. Even if most collectors today know that they ought to just put it in a box, the urge to rebind is powerful. I have felt it myself. And for me, missing leaves tend to be a dealbreaker unless the item is so scarce that no other copy is likely to surface. But then again, I have several times purchased inexpensive books with missing leaves painstakingly replaced in manuscript by an early owner. I did this partly because of a weakness for manuscripts, but also partly because such repairs tell me something about book owners in the early modern period, and how they cherished even small, relatively cheap books. It’s a far cry from the disposable object that the new book has become in the modern era.

Would I buy multiple copies of the same work, damaged or not, just to compare them across printers or time periods? Yes, I’ve already started some collections of this kind (though I balk at acquiring the damaged items). Would I pay attention to ephemera, if it is related to my collecting themes? Of course. Do I currently seek it out? Perhaps not. One of the burning questions, though, is whether the Zinman magic can be duplicated. On reading about “critical mass theory,” I was reminded of the Greek myth about the witch Medea, who demonstrated her rejuvenating powers to the three daughters of old King Pelias. She took an aged ram, cut him up and threw the pieces into a cauldron. To the bubbling mess she added herbs, and over it she chanted incantations. Suddenly, a vigorous young lamb climbed from the pot! So the three daughters of Pelias cut their father up, put the pieces into a cauldron, cast into it the herbs supplied by Medea, and chanted the prescribed incantations. And…nothing happened.

In other words, what if I spend a huge amount of time and money amassing a collection of disbound, imperfect, decaying items, and…nothing happens? Clearly this approach involves a leap of faith, but more importantly, one should undertake it only if one possesses (1) a deep love for the material and (2) the fortitude to persist in winkling out items that booksellers have long ago set aside as unsaleable. Perhaps, too, one needs an instinctive feel for material that will yield a critical mess, that is, material which others will find interesting once you have assembled it and pointed to the new insights it yields. What are the critical messes of the future?

Read this book for the laughs, read it as the long-awaited story of a great American collector, and most importantly, read it to stimulate your own thinking about the act of collecting.

Jennifer Larson is Professor of Classics at Kent State University, past Chair of FABS and current editor of the FABS Journal. She collects small-format books from the Handpress Era and is a member of several bibliophilic societies including The Miniature Book Society and The Grolier Club.