By Enrique Vazquez

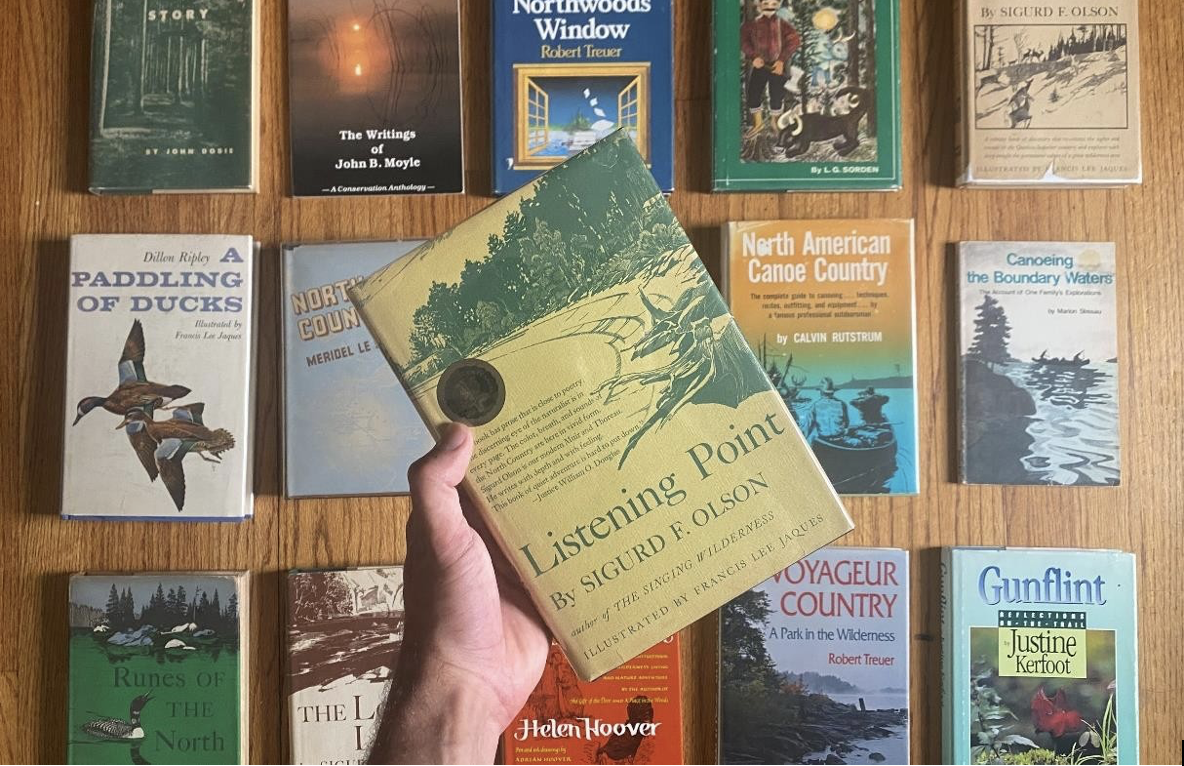

An overview of notable titles. Listening Point was the primary inspiration for the collection.

The Boundary Water Canoe Area (BWCA) is a protected chain-of-lakes spanning over one million acres along the Minnesota-Canada border. It was here that my family brought me to camp at a young age, and that I learned to love the woods. At trail’s end we would always visit Listening Point—a rock spit where famed author and conservationist Sigurd F. Olson spent much time. It is tradition to sit at Olson’s point and reflect on one’s travels. As Olson wrote in Listening Point (Knopf 1974), “Only when one is aware and still, can things be seen and heard.”

Indeed, it is in those north woods that I have heard the laughter of friends, the groans of canoe portages, and the whisper of campfire stories. It is here I have learned the hard lessons of a flipped canoe and the perseverance required for a long day’s paddle. It is at Listening Point that these stories are realized and allowed to join those of the canoers and hikers that came before.

While my book collection’s origin is in Olson’s work, it also includes the books of numerous wilderness writers from the region. This selection of 35 books, titled “Tales of the Midwestern Northwoods,” focuses on the Minnesota Boundary Waters, the Mississippi River, and the white pine forests of Wisconsin. Its narrators are many and diverse, including conservationists, outdoorsmen (both real and imagined), indigenous peoples, trailblazing women, artists, loggers, and families like mine. Such an assemblage is in keeping with Olson’s philosophy that the wilderness should be shared and made accessible to all.

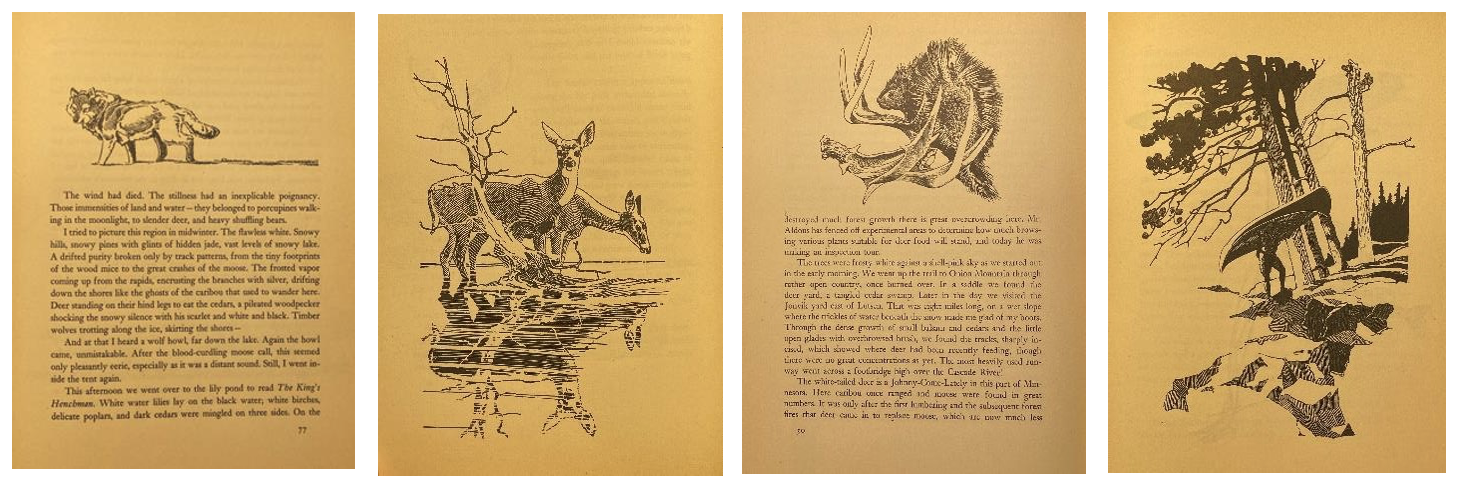

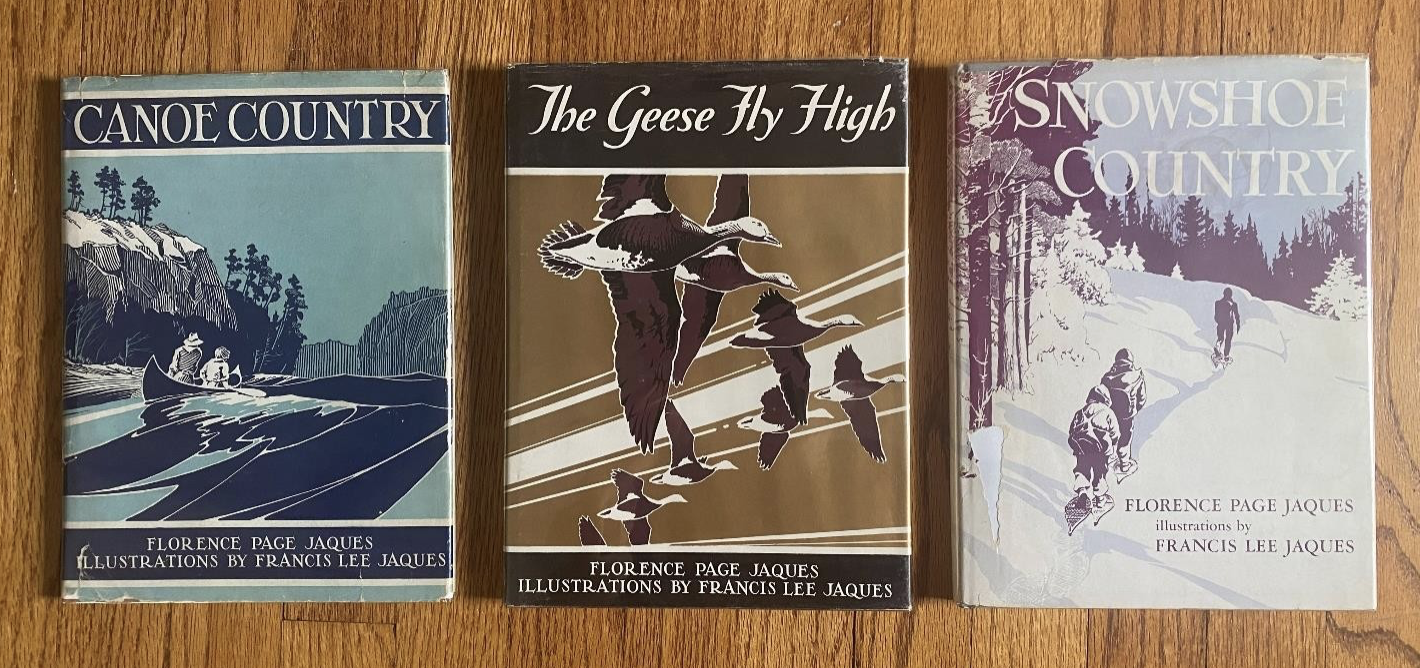

As a teen I would read Olson’s works over the long Minnesota winters, turning to his descriptions of summer days spent paddling. His imagery was vivid—aided by beautiful illustrations which he sourced from local painter Francis Lee Jaques. Lee’s art is omnipresent in Minnesota. He illustrated a series of well-known books written by his wife, Florence, and he painted multiple life-size dioramas for the Twin Cities’ Bell Museum of Natural History. Elementary school field trips to the museum would always culminate by staring in awe at a Lee’s diorama of a wolf pack overlooking Lake Superior. Such evocative depictions of the outdoors are what drove me to camp throughout my youth, in hopes that one day I might live a scene from one of those books or exhibits.

The Bell Museum of Natural History’s Wolves at Shovel Point diorama. Background art by Francis Lee Jaques.

It was only years later, and after countless trails, that wolves again confronted me. Having moved to the east coast for college, the last thing I was expecting to see were the images of my youth, but in the New York Museum of Natural History’s Hall of North American Mammals, I found Lee once more. Amid the Hall’s exhibits, many of which Lee had painted, another wolf diorama brought pangs of homesickness and an urge to return to the texts of my childhood.

Spot illustrations by Francis Lee Jaques from various Olson books in the collection.

Finding such regionally specific books on the east coast proved difficult, and so the majority of my collecting was relegated to school breaks and summers when I was back visiting family. None of the books in my collection have been purchased online—all of my titles were bought over the past four years in used bookstores or flea markets, most for under $15. While this in-person-only rule is partially born out of practicality (there is a small market for these books and as a result few online listings), it also stems from the spirit of exploration. It seemed only fitting that to buy books detailing others’ rugged escapades I should be required to do a bit of digging.

In book hunting I also discovered the works of the authors who drew inspiration from Olson and Francis & Florence Jaques. For instance, it was in a used bookstore that I was recommended Sam Cook’s Quiet Magic and at a Duluth church sale that I stumbled across another husband-wife team in the Hoovers’ The Years of the Forest. I also was able to find unique editions that I’d never seen before. For instance, a large illustrated copy of Aldo Leopold’s seminal A Sand County Almanac, and a copy of A Paddling of Ducks with the book plate of one of Olson’s later illustrators Lesli Kouba were both pulled from a dusty book pile at a garage sale. It never ceased to amaze me how I could find some of the best books in the most surprising places.

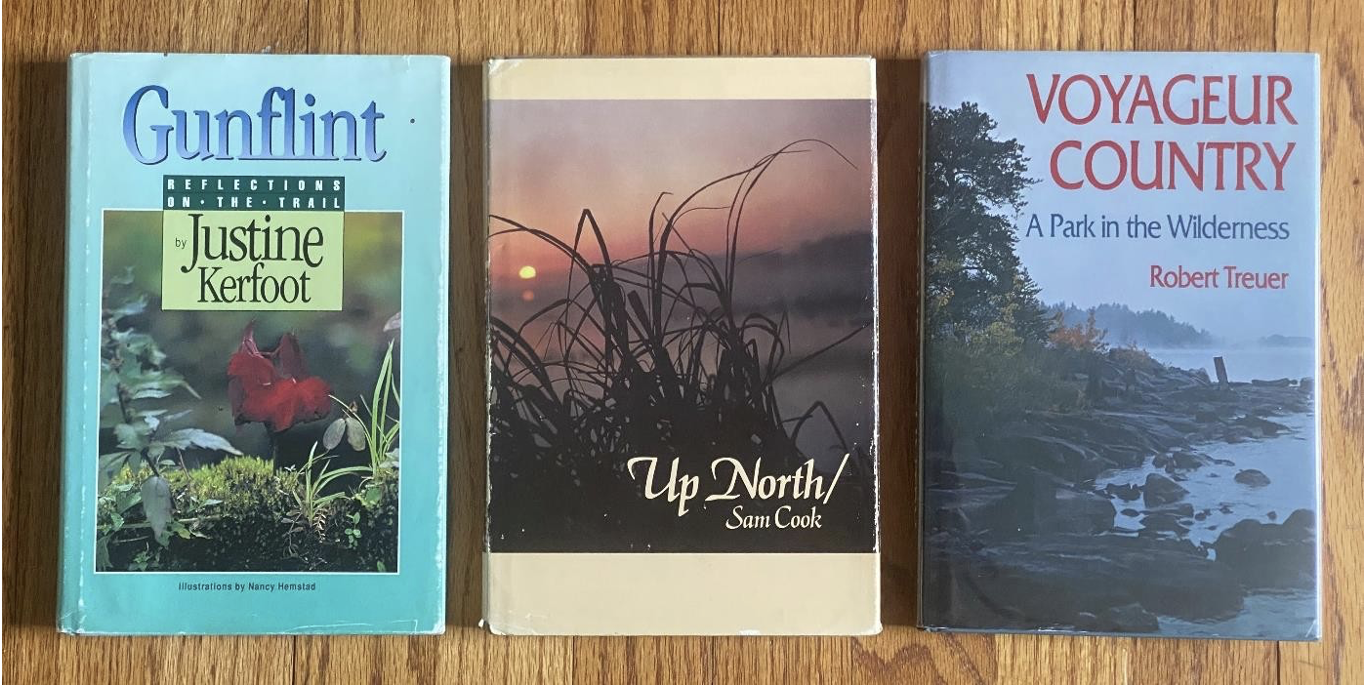

Other notable titles focused on describing the region. Authors include Justine Kerfoot, Sam Cook, and Robert Treuer.

As my collection has grown, I have found myself drawn to older editions—both because they added a challenge to collecting, but also because there is little existing information on how this regional writing style developed. I have been unable to find an index of the wilderness memoirs written about this region, and part of my drive for collecting is to catalogue books that were locally printed or self- published amid the environmental movement of the 1960’s. Examples in this collection include publications by the Wisconsin House, Prairie Oak, or Voyageur Press. I aim to publish an index of these books in the coming months, ensuring that these stories are made more accessible to future readers.

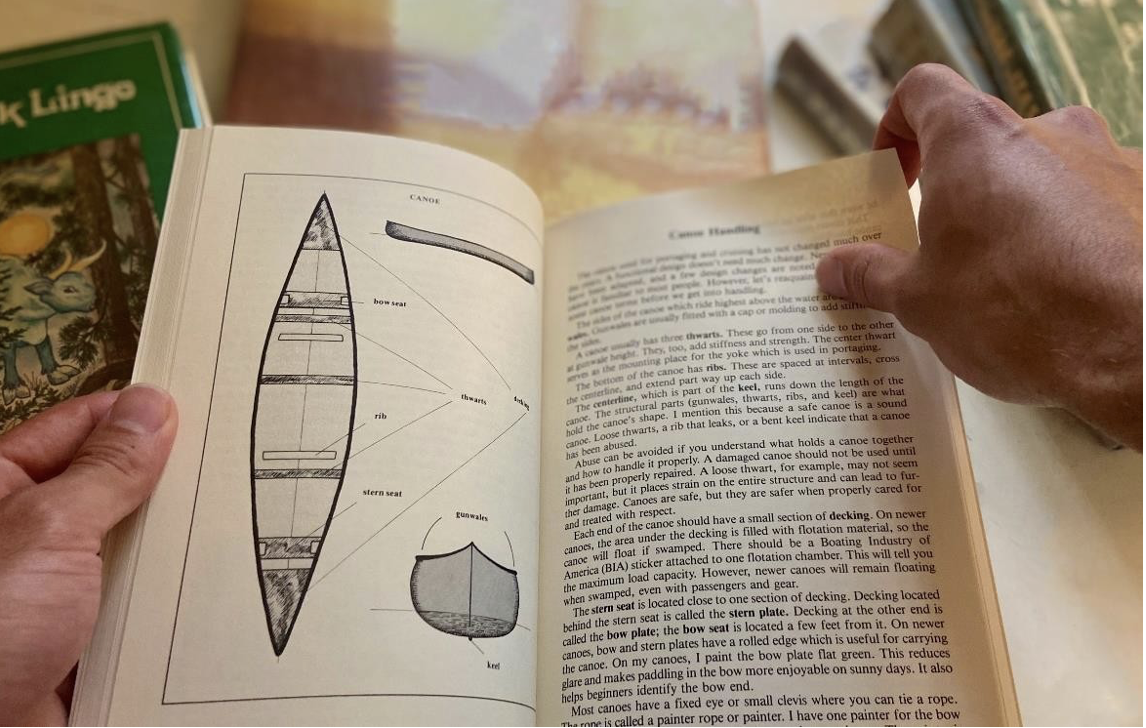

No doubt the writers who followed in the footsteps of Olson and Leopold found traction in the popularity of the 1970’s “woodsman” aesthetic. To capitalize on a renewed interest in back-to-nature lifestyles these authors began to market themselves as the archetypal woodsman: strong, independent men who could survive in any wilderness condition. Books like Harry Drabik’s Guide to Wilderness Canoe Camping and North American Canoe Camping are full of self-promotional headshots as these authors attempted to become household names with little success.

Diagram from Harry Drabik’s Guide to Wilderness Canoe Camping.

Still, the Midwest woodsman’s regionally distinct identity (vis-a-vis red flannels) is owed to the area’s early loggers, who ironically sought to clear the very wilderness that naturalists like Leopold and Olson were fighting to protect. Indeed, the outdoor culture of the Midwest has also been shaped by the region’s long relationship with the timber industry, and books played a large role in advancing a competing vision for the outdoors—one which advocated for mastery over the natural world rather than co-existence.

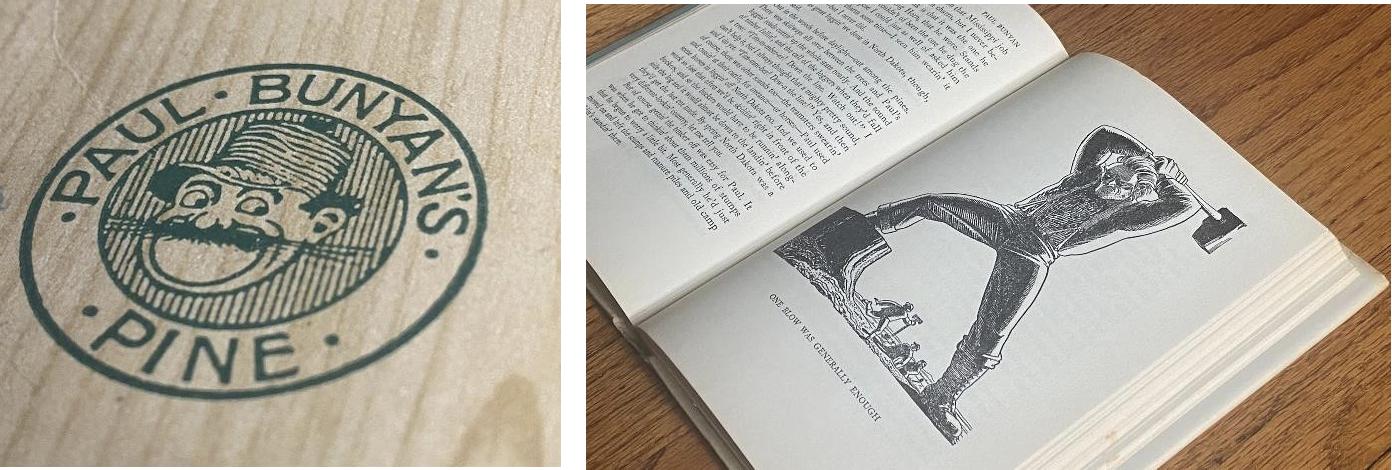

Left, the Red River Lumber Company’s Paul Bunyan Logo from What Say You of Paul. Right, illustration of Bunyan by Rockwell Kent from Esther Shephard’s Paul Bunyan.

No example is more poignant than the folk hero Paul Bunyan, a larger-than-life lumberjack who could literally mold the American landscape to his will. Stories of Bunyan began to spread in logging camps in the upper Midwest and modern day BWCA around the turn of the century. However, lumber companies, like the Red River Lumber company of Minneapolis, soon co-opted these stories for marketing purposes. In 1916 Red River turned Paul Bunyan into the mascot for their new line of white pine timber, embellishing what were originally believable stories to make them more interesting to the public. Paul soon grew from a seven-foot man to a mountain-sized giant whose footprints filled with water to become the great lakes.

It was through Red River Lumber pamphlets that Paul became widely known in popular culture. While the original pamphlets are exceedingly rare, this collection contains a later pamphlet from the company titled What Say You of Paul? which ironically attempts to catalogue “the real true stories of Paul,” many of which were fabricated by the company only years prior. Other authors attempted to meet with loggers and hear the original tales. One such example, Esther Shephard’s Paul Bunyan, was originally published in 1924 and then later reprinted with illustrations amid the legend’s spike in popularity in the 60’s. Still at the time of initial printing the Red River stories had already permeated lumber camps, canonizing many of Paul’s “fakelore” tales.

Early editions by Florence Page Jaques; cover art by Francis Lee Jaques.

These conflicts, between industrial and folk narrative, between speculator and conservationist have not ended. Recent debates over whether to open the BWCA to copper mining, or if regulation is needed to protect species from climate change are still unresolved. So too are questions being asked about whether the wilderness is truly accessible to all—BWCA permits have been restricted in recent years in response to over-camping. As much as this collection is a celebration of the region’s beauty, it is also an attempt to grapple with these concerns.

When Aldo Leopold coined the term “Land Ethic” in Sand County Almanac, he was attempting to define the moral responsibility that humans have to the natural world. My book collection demonstrates that living to such standards demands a balance between preservation and development. The future of the Midwest and its wilderness is dependent on cataloguing and understanding the stories of those who have come before. Much like sitting at Listening Point, my collection is an attempt to reflect on this region’s journey towards a more accessible wilderness— through exposure to books about the very trees that made them.

Enrique Vazquez is a Minnesotan native and a recipient of the 2023 National Collegiate Book Collecting Prize. He is a recent graduate of Yale College where he was a member of the Elizabethan Club for book collecting. His bibliophilic interests focus on wilderness writing, Americana, and the history of medicine and science.

2 thoughts on “Tales of the Midwestern Northwoods”

This is a treasure. For the books. For the love of the Boundary Waters.

Thank you for the feedback, Kathleen! I’ll pass your comment on to Enrique.